Most of us set goals for ourselves to do things that are difficult for us to do. Instead, how about setting goals to work hard at something that is actually a pleasure?

It’s clear that the deep, fulfilling experiences in life are when we are very focused at what we really enjoy doing. So goals should start with that premise, and aim to create more of that in our lives. Here are five steps to create goals that encourage you to do more of what you love.

1. Stop thinking about the goal, and start thinking about the process.

The things that matter most for success in life is how hard you work at what you want to achieve, according to research reported in Scientific American. So formulate goals that focus on working hard at something you like working at.

For a lot of us this means we need a bit of self-discovery. What are we great at? What do we love doing? If you are not spending a lot of time and energy on what you think you should spend it on, then maybe that’s not quite right for you.

The act of being lost in this world is actually the process of figuring out what are appropriate goals for ourselves. Where should we spend our time developing our talents? Read more

There is no other way to figure out where you belong than to make time to do it and give yourself space to fail, give yourself time to be lost. If you think you have to get it right the first time, you won’t have the space really to investigate, and you’ll convince yourself that something is right when it’s not. And then you’ll have a quarterlife crisis when you realize that you lied to yourself so you could feel stable instead of investigating. Here's how to avoid that outcome.

1. Take time to figure out what you love to do.

When I graduated from college, I was shocked to find out that I just spent 18 years getting an education and the only jobs offered to me sucked. Everything was some version of creating a new filing system for someone who is important.

Often bad situations bring on our most creative solutions. And this was one of those times: I asked myself, “What do I want to do most in the world, if I could do anything?” I decided it was to play volleyball, so I went to Los Angeles to figure out how to play on the professional beach circuit. Read more

There's a huge market for telling women how to be happier. Maybe it's because women read more than men. Or maybe it's the discrepancy that women know when they are overweight and men don't. Or the discrepancy that most men think they are good parents and most women think they need to be better parents. The list goes on and on, in a glass-half-empty kind of way.

In general, I think the strength of women is that they see things more clearly. Yes, it's a glass-half-empty world for women, compared to men, but women should leverage their stronger grip on reality. So here's my contribution to women and clarity. I am debunking five totally annoying pieces of advice I hear people give women all the time.

1. Take a look at the lists of best companies for women to work for

This is an advertising ploy, not a plan for you to run your life. Every single time there's a list like this, women write to me from the companies on the list to tell me how much they suck for women. But it's not like I need those emails. I can just look at senior management, which is almost always all men, and see that corporate careers are set up for a one kind of life: very focused, no other interests, except, maybe, oneself. And this is not all that appealing to most women.

So you can forget the lists. The bar is so low to get on the lists that which company is on and which company is off is statistically irrelevant to women planning their careers. Read more

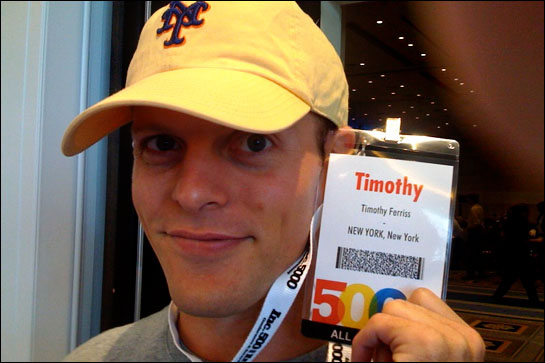

I have hated Tim Ferriss for a long time. I have hated him since we both had editors at Crown Publishing who sat next to each other and I heard how difficult he is.

I didn’t blog about it because first of all, I’m sure the buzz about me is that I’m difficult, too. And also, his book, The 4-Hour Workweek, was a bestseller and mine wasn’t. So I figured people would say that I’m jealous. And really, what author is not jealous sometimes? I mean, every author wants to write a bestseller.

But at this point, two years later, my hatred goes way beyond jealousy. My hatred is more selfless than that. And while I do understand that Tim is great at accelerated learning, the time management tips I have learned from him stem from the energy I have spent hating him:

1.Don’t hang out with people who don’t respect your time

This all started at SXSW conference in 2007, right before Tim’s book came out, when he was promoting the hell out of it to bloggers. Of course, this was not a bad idea, and to be fair, Tim was brilliant to start this book marketing trend. But that is beside the point. He approached me after my panel and said, “Can I get you coffee? I’d love to talk with you.”

I said, “Uh. No. I have plans.”

And he asked who with. Read more

It is well known in the sex research arena that the more educated a woman is the more often she will receive oral sex.

I have always wondered if this is true for salary as well. For example, if your salary goes up by $50,000, how much more likely are you to receive oral sex?

I cannot find research to support that women who earn more receive more oral sex, which is why I am conducting my own research on this week's poll.

But I have a hunch, based on a string of research that I have cobbled together: Read more

My company is out of money, which you are never supposed let happen. And definitely never supposed to confess to. Because then investors can give you any terms they want. Rape. Carnage. Pillage. Everything. And in our case, it’s coming from the angels who invested in our first round of funding, which means that the people who are supposed to be on our side are killing us.

So two days before Christmas, I am going nuts, trying to close a bridge financing from the angel investors who funded us initially. Which means that these guys are very rich, and traveling for Christmas, and totally not interested in being bothered with the minutia of our depleted finances.

I’m desperate. We’ve already skipped one payroll, and it’s hard to think of a worse time to do that than the week before Christmas.

When 70% of young people say they want to run their own business, they are probably not thinking they will fund their business themselves. Since they probably have no money. So they are looking at taking in investors. But I’m not sure that 70% of young people want to take in angel investors, because here’s what it looks like:

1. You are on the phone all the time.

Tuesday before Christmas: I am glued to my phone: Investors don’t work on a schedule. They are millionaires. They are trying to sail their boat in Bermuda but they live in Wisconsin which means they have to make ten connecting flights from snowbound airports, and my chances of catching them between flights are slim. So I spend my day waiting for someone to call in with another clever idea for taking more equity from the company and redistributing it to the investors.

2. You’re always sick, but not take-a-day-off-work sick

And I have pinkeye. It started on Monday, when 20/20 was in our office to do a story on salary. Yep. That’s right. The company that is not paying salaries right now is featured on 20/20 as the poster child for transparent salaries.

The camera is right in my face while I’m talking about how the only people who benefit from hidden salaries are managers who made hiring mistakes and don’t want to fix them. “Management should not hide behind their weaknesses,” I say. And then I say, “Do you have something in that camera that can fix my pink eye?” Read more

One of the reasons my column runs in more than 200 newspapers is that I send out one blog post a week to about 1000 editors. I have to do the list manually because, big surprise, most editors at most papers do not subscribe to blogs.

Today I was besieged by out of the office responses. Of course, everyone is out of the office. Very little news happens between Christmas and New Year's that you can't predict and write beforehand.

The time between Christmas and New Year's is a great time for you to take things into your own hands. During this time, almost all of senior management is completely checked out in most industries. After all, this is what senior is all about — getting to go where you want to at the end of December. So you might find that there are opportunities to get a big break. Read more

The process of picking the best posts of 2008 is actually very subjective. But I do think that year-end lists are a good way to look at the conversations we have had this year, and how our thinking has changed both personally and collectively.

Posts about my divorce weren’t my most popular, but I learned the most from them:

A Case Study in Staying Resilient: My Divorce Feb. 2008 (131)

I was scared to post an announcement about my divorce because I was in the middle of raising our first round of funding, and I thought I’d freak out investors. But I was more scared that if I stopped posting about myself I’d ruin the blog and my desire to write it. So I followed this post five seconds later with one about me being on CNN in an effort to distract investors. It turned out that investors were much more interested in divorce than CNN, and I realized that I was being rewarded by investors for being true to myself. Bonus: We raised $700,000 in funding.

Keeping an Eye on My Career While I go through a Divorce May 2008 (95)

The New York Times wrote about my divorce and questioned whether I should be blogging about it. My divorce lawyer told me I was going to jeopardize my settlement by blogging. “You look reckless,” he told me. I decided that I was willing to lose money in the settlement to be able to keep writing about my life. Addendum: My almost-ex-husband never complained about the blog.

Posts about the farmer were also not my most popular. But they were the most exciting for me to write. It’s been a year full of soul-searching about a lot of things in my life, including this blog. I knew I didn’t want to 500 posts on how to write a good resume. But I knew I wanted to still write about the intersection of work and life. The farmer gave me the opportunity to try something new. And these posts ended up opening a larger conversation among you guys about what I should be writing on the blog — input and insight that I really appreciate.

A New Way to Measure Blog ROI June 2008 (112)

How I Started Taming My Workaholic Tendencies June 2008 (136)

Vulnerability is the Key to Likability at Work (and on the Farm) Aug. 2008 (104)

Self-Sabotage is Never Limited to Just One Area of Your Life Oct. 2008 (47)

How to Go to a Meeting When You Want to Sit Home and Cry Nov. 2008 (103)

This is the list you were probably expecting. Before I got sidetracked:

Subjectively popular posts of 2008

The Hardest Part of My Job is that Everyone Lies about Parenting June 2008 (161)

Plastic Surgery is the Next Must-Have Career Tool, Maybe May 2008 (126)

Advice from the Top: Marry a Stay-at-Home Spouse or Buy the Equivalent May 2008 (168)

7 Reasons Why Graduate School is Outdated June 2008 (135)

Living Up to Your Potential is BS June 2008 (202)

My Annual Rant about Christmas at Work Dec. 2008 (187)

Post that generated the most thank-you notes:

How to Answer the Toughest Interview Question Feb. 2008 (117)

Post that I cried the most while I wrote:

The Part of Postpartum Depression that No one Talks About Feb. 2008 (102)

Post with the most diatribes in the comments section:

Writing Without Typos is Totally Outdated May 2008 (151)

Post that generated the most interviews from mainstream media:

Give Thanks that there is No Job Shortage for Young People Nov. 2008 (115)

Most popular guest post:

Twentysomething: Why My Generation is More Productive than Yours Sept. 2008 (140)

Thank you so much for all your comments and emails. The blog continues to be my favorite part of my job. And maybe my favorite job that I’ve ever had.

Last year, the most commented-on post here was Five Things People Say about Christmas that Drive Me Nuts. And the year before that, the piece that made the most newspaper editors cancel my column was, Christmas at the Office is Bad for Diversity.

In general, my point on the Christmas stuff is that religious holidays don't belong at work, and that people who don't celebrate Christmas should not be forced to use one of their religious holidays on Christmas. Why do I use a floating holiday for Yom Kippur and no one uses a floating holiday for Christmas? It's preferential religious treatment and there is no reason for it when you can give each employee x number of days off to use as he or she chooses.

Before you complain about this line of reasoning, please click on the links and read the posts I linked to above. Then you can argue.

I know that you guys have a lot to say about Christmas, not just because of the comments these posts receive, but also because over the years I have found that for the most part, Christians comment publicly, and Jews send private emails to me. Read more

Most people who are on top of their game respond to most emails within 48 hours. However some emails are so terribly written that it's actually impossible to send an answer. Other emails are so terribly written that the amount of time it would take to figure out what to answer is simply not worth it.

In order to get the response you're looking for, you need to ask a very good question. Here are five ways to do that:

1. Don't send an essay. Your whole email should not exceed five sentences. If you need to give the person a lot of information in order to help you, send them an email asking if you can send more information. But here's a tip: You're most likely to get a response if you don't need to send more information. A direct question is easiest to answer, and it doesn't take a lot of space.

2. Don't be vague. Here's an interesting question: “Is there a god?” But it's not a question for email, because any answer would be very long and philosophical. For this question, go buy a book. But that’s not even the worst type of offender. At least “Is there a god” is a short, direct question. Emails that call loudest for the delete button are those with vague requests for help followed by a long-winded personal introduction and no real question. Test yourself: Write a concise subject line, and then go back to the email and delete anything not directly related to that. Read more