We all know that people judge each other in the first five seconds they see each other. We talk about clothes, and weight , and tone of voice. But you can also judge someone by their walk.

Don't tell me this is shallow. You can't help but judge people by their gait. But the good news is that we are very good at judging people on first impressions (sponsor link: download movies). It's probably a survival skill we developed very early on as humans — before you could Google someone to know their credibility. And when it comes to gait, it is possible that we each have a unique gait, like a unique thumbprint. (Yes, people are developing security technology based on gait: Cool, right?)

I am convinced that you can change how you function in the world by changing your gait. We already know that people with the most control over their image work hard on understanding the body language they project. For example, if you feel defensive, resist the temptation to fold your arms in front of your chest and the person you're talking to will think you are listening better. And, in fact, you will be listening better because based on your physical urge to fold your arms you gained intellectual awareness that you are feeling defensive. Read more

Ryan calls me from the office. I say, “Don’t talk to me now. I’m sulking.”

He says, “Okay. What are we doing about the five-year sales projections?”

I say, “I told you. I need ten minutes.”

“Nothing is going to change in ten minutes,”

“In ten minutes I'll be more pleasant on the phone.”

“Okay.” He hangs up.

I eat two waffles and then I write on the calendar how many calories I can eat for the rest of the week to make up for the waffles. Then I take out two more waffles and while they’re cooking, I change all the numbers on the calendar.

Then I look at my email, and there is another missive from Guy Kawasaki telling me that I am underutilizing Twitter. He even took a picture of two tweets he thinks I should respond to. He sent the picture to me.

He thinks I should give 140-character career advice.

Here’s some advice I think of immediately: Read more

It's a big day, and I'm excited to take a pause from work with the rest of the country to watch Barack Obama give his inagural speech.

In the meantime, I'm thinking about the day of service. How Obama wants the country to come together in the name of service. And I heard MTV declare, last night, that the next generation is Generation S. For service.

So I'm thinking about service, and how all our efforts to help people, really, are aimed to make them more indepdent. And that's what work is about: Taking care of ourselves, mentally and financially.

When you mentor someone in the work arena, you are providing that service. So often we pick the superstar to mentor. Or the up-and-comer. Or the one who can help us with our own networking. But you can use your work skills to help someone pull themselves out of a bad spot. A really bad spot. Work skills are very powerful. And so is mentoring.

So when you think about service, don't' think of it as separate from work. Obama stands for all the things that we do, on this blog: Personal responsibility, transparency, honesty, change even when it's difficult. This inagural day is the beginning of meshing the public life and worklife so that we are living the values we believe in, wherever we go.

Think about how you can focus on service at work. Each of us has a lot of tools at our disposal. If we take the time to use them.

Most of us set goals for ourselves to do things that are difficult for us to do. Instead, how about setting goals to work hard at something that is actually a pleasure?

It’s clear that the deep, fulfilling experiences in life are when we are very focused at what we really enjoy doing. So goals should start with that premise, and aim to create more of that in our lives. Here are five steps to create goals that encourage you to do more of what you love.

1. Stop thinking about the goal, and start thinking about the process.

The things that matter most for success in life is how hard you work at what you want to achieve, according to research reported in Scientific American. So formulate goals that focus on working hard at something you like working at.

For a lot of us this means we need a bit of self-discovery. What are we great at? What do we love doing? If you are not spending a lot of time and energy on what you think you should spend it on, then maybe that’s not quite right for you.

The act of being lost in this world is actually the process of figuring out what are appropriate goals for ourselves. Where should we spend our time developing our talents? Read more

There is no other way to figure out where you belong than to make time to do it and give yourself space to fail, give yourself time to be lost. If you think you have to get it right the first time, you won’t have the space really to investigate, and you’ll convince yourself that something is right when it’s not. And then you’ll have a quarterlife crisis when you realize that you lied to yourself so you could feel stable instead of investigating. Here's how to avoid that outcome.

1. Take time to figure out what you love to do.

When I graduated from college, I was shocked to find out that I just spent 18 years getting an education and the only jobs offered to me sucked. Everything was some version of creating a new filing system for someone who is important.

Often bad situations bring on our most creative solutions. And this was one of those times: I asked myself, “What do I want to do most in the world, if I could do anything?” I decided it was to play volleyball, so I went to Los Angeles to figure out how to play on the professional beach circuit. Read more

There's a huge market for telling women how to be happier. Maybe it's because women read more than men. Or maybe it's the discrepancy that women know when they are overweight and men don't. Or the discrepancy that most men think they are good parents and most women think they need to be better parents. The list goes on and on, in a glass-half-empty kind of way.

In general, I think the strength of women is that they see things more clearly. Yes, it's a glass-half-empty world for women, compared to men, but women should leverage their stronger grip on reality. So here's my contribution to women and clarity. I am debunking five totally annoying pieces of advice I hear people give women all the time.

1. Take a look at the lists of best companies for women to work for

This is an advertising ploy, not a plan for you to run your life. Every single time there's a list like this, women write to me from the companies on the list to tell me how much they suck for women. But it's not like I need those emails. I can just look at senior management, which is almost always all men, and see that corporate careers are set up for a one kind of life: very focused, no other interests, except, maybe, oneself. And this is not all that appealing to most women.

So you can forget the lists. The bar is so low to get on the lists that which company is on and which company is off is statistically irrelevant to women planning their careers. Read more

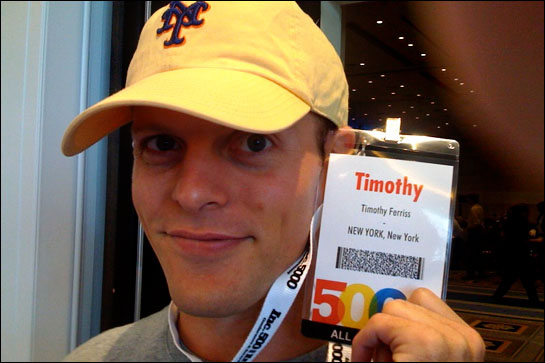

I have hated Tim Ferriss for a long time. I have hated him since we both had editors at Crown Publishing who sat next to each other and I heard how difficult he is.

I didn’t blog about it because first of all, I’m sure the buzz about me is that I’m difficult, too. And also, his book, The 4-Hour Workweek, was a bestseller and mine wasn’t. So I figured people would say that I’m jealous. And really, what author is not jealous sometimes? I mean, every author wants to write a bestseller.

But at this point, two years later, my hatred goes way beyond jealousy. My hatred is more selfless than that. And while I do understand that Tim is great at accelerated learning, the time management tips I have learned from him stem from the energy I have spent hating him:

1.Don’t hang out with people who don’t respect your time

This all started at SXSW conference in 2007, right before Tim’s book came out, when he was promoting the hell out of it to bloggers. Of course, this was not a bad idea, and to be fair, Tim was brilliant to start this book marketing trend. But that is beside the point. He approached me after my panel and said, “Can I get you coffee? I’d love to talk with you.”

I said, “Uh. No. I have plans.”

And he asked who with. Read more

It is well known in the sex research arena that the more educated a woman is the more often she will receive oral sex.

I have always wondered if this is true for salary as well. For example, if your salary goes up by $50,000, how much more likely are you to receive oral sex?

I cannot find research to support that women who earn more receive more oral sex, which is why I am conducting my own research on this week's poll.

But I have a hunch, based on a string of research that I have cobbled together: Read more

My company is out of money, which you are never supposed let happen. And definitely never supposed to confess to. Because then investors can give you any terms they want. Rape. Carnage. Pillage. Everything. And in our case, it’s coming from the angels who invested in our first round of funding, which means that the people who are supposed to be on our side are killing us.

So two days before Christmas, I am going nuts, trying to close a bridge financing from the angel investors who funded us initially. Which means that these guys are very rich, and traveling for Christmas, and totally not interested in being bothered with the minutia of our depleted finances.

I’m desperate. We’ve already skipped one payroll, and it’s hard to think of a worse time to do that than the week before Christmas.

When 70% of young people say they want to run their own business, they are probably not thinking they will fund their business themselves. Since they probably have no money. So they are looking at taking in investors. But I’m not sure that 70% of young people want to take in angel investors, because here’s what it looks like:

1. You are on the phone all the time.

Tuesday before Christmas: I am glued to my phone: Investors don’t work on a schedule. They are millionaires. They are trying to sail their boat in Bermuda but they live in Wisconsin which means they have to make ten connecting flights from snowbound airports, and my chances of catching them between flights are slim. So I spend my day waiting for someone to call in with another clever idea for taking more equity from the company and redistributing it to the investors.

2. You’re always sick, but not take-a-day-off-work sick

And I have pinkeye. It started on Monday, when 20/20 was in our office to do a story on salary. Yep. That’s right. The company that is not paying salaries right now is featured on 20/20 as the poster child for transparent salaries.

The camera is right in my face while I’m talking about how the only people who benefit from hidden salaries are managers who made hiring mistakes and don’t want to fix them. “Management should not hide behind their weaknesses,” I say. And then I say, “Do you have something in that camera that can fix my pink eye?” Read more

One of the reasons my column runs in more than 200 newspapers is that I send out one blog post a week to about 1000 editors. I have to do the list manually because, big surprise, most editors at most papers do not subscribe to blogs.

Today I was besieged by out of the office responses. Of course, everyone is out of the office. Very little news happens between Christmas and New Year's that you can't predict and write beforehand.

The time between Christmas and New Year's is a great time for you to take things into your own hands. During this time, almost all of senior management is completely checked out in most industries. After all, this is what senior is all about — getting to go where you want to at the end of December. So you might find that there are opportunities to get a big break. Read more